Simples vs. Composto

So what is the gerúndiogerund exactly?

For English speakers, it generally corresponds to the verb form ending in -ing, when it is used as a noun (e.g. “I like cooking“). However, the Portuguese gerund plays a different role, which is actually more similar to the English present participle.

The Portuguese gerund has 2 forms:

- simples (simple): Refers to the process of an action and ends in –ndo – This is the type we’ll cover in this Learning Note!

- composto (compound): Refers to an event that took place before the main clause, using the construction gerúndio + particípio passado

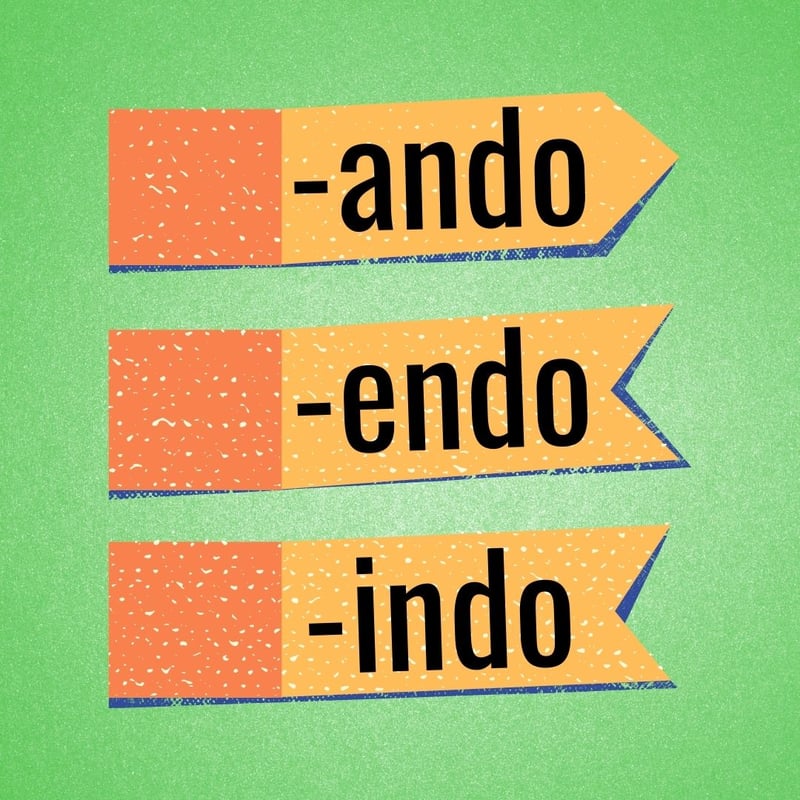

How to Form the Gerúndio

The gerúndio is one of the 3 formas nominais dos verbos (nominal verb forms), along with the impersonal infinitive and the past participle. These forms do not indicate verb tense, mood, or person on their own. They depend on context (i.e. the surrounding conjugated verbs) for that.

The gerúndio is invariable (it doesn’t change according to gender or number) and it’s formed the same way for both regular and irregular verbs. You simply take the infinitive form, remove the r, and append –ndo. For example:

Don’t Use It As A Noun

Be careful! Despite the literal translation of “gerund”, grammatically it corresponds more closely to the English present participle. Unlike the English gerund, the Portuguese gerúndio cannot act as a noun. For example:

- ❌ Fumando faz mal à saúde – Incorrect. The gerúndio cannot be used here as a noun.

- ✅ Fumar faz mal à saúdeSmoking is harmful to your health – Correct. Use the infinitive verb form here instead. This refers to “the act of smoking” as a noun.

The Gerúndio in European Portuguese

You may recall from the present continuous unit, that there are some differences in how the gerúndio is used among the different Portuguese dialects. For example, in European Portuguese, you typically don’t use the gerúndio for the present continuous. Just to quickly review:

- In European Portuguese, the present continuous / present progressive is typically formed with estar + a + the infinitive. For example: Eu estou a estudar gramática.I am studying grammar.

- In Brazilian Portuguese, the gerund is used here instead: Eu estou estudando gramática. As you can see, the BP variation is more similar to the English “I am studying grammar” than the EP one.

That said, although it’s not very common, there is still a time and place for the gerúndio in European Portuguese! In EP, the gerúndio simples is generally used in 3 ways:

- As a gerúndio adverbial (adverbial gerund) within a dependent clause or

- connecting 2 coordinated clauses (as a replacement of the conjunction eand )

- Expressing progress / gradualness, with the help of the auxiliary verb ir (the most common use case ⭐️ )

(The adverbial uses are less common in Brazilian and African dialects of Portuguese.)

Start familiarizing yourself with the gerúndio by exploring examples of each of the primary uses below. We’ll also mention more popular alternatives to using the gerúndio (when relevant) throughout the rest of this Learning Note.

Adverbial Gerund in Dependent Clauses

Orações gerundivas (short for orações subordinadas adverbiais gerundivas) are dependent clauses in which the verb is in the gerúndio and that function like an adverb to the main clause. They can hold the semantic value of manner, time, causality, consequence, condition, and concession (or sometimes a combination of multiple values). Again, don’t confuse this with “gerund phrases” in English grammar, which function as a noun.

Orações gerundivas (short for orações subordinadas adverbiais gerundivas) are dependent clauses in which the verb is in the gerúndio and that function like an adverb to the main clause. They can hold the semantic value of manner, time, causality, consequence, condition, and concession (or sometimes a combination of multiple values). Again, don’t confuse this with “gerund phrases” in English grammar, which function as a noun.

It’s more common to see these clauses at the beginning of a sentence, but they can appear in the middle or at the end as well. Let’s see some examples of each type:

Manner

Some adverbs characterize the manner or way an action takes place, such as: depressaquickly , bemwell , lentamenteslowly , etc.

With gerundive clauses, you can also characterize the mode or manner in which an action, such as running or speaking, takes place:

- Ele foi até casa, correndo pela cidadeHe went home, running through the city – The way he went home (manner of travel) was by running through the city.

- Já vou! - disse o Pedro, bocejandoBe right there! - said Pedro, yawning

- The gerund with the value of manner is mostly used in the 3rd person, as if narrating an event.

Time

Instead of using conjunctions such as depoislater, then, after or a seguirsubsequently, next, after, following , you can convey temporal relationships using the gerund. This could indicate something happening before, after, or at the same time.

- Deitando-se na cama, a Maria adormeceuAs she lay on the bed, Maria fell asleep – She lay down before falling asleep.

- A Maria tropeçou, partindo os pratosMaria stumbled, breaking the plates – She broke the plates right after stumbling.

Causality

The gerúndio can also appear in clauses that indicate the cause of the action expressed in the main clause. The gerundive clause can appear at the beginning or at the end of the sentence. Instead of using conjunctions such as porquebecause , comoas, since, like , dado quesince , etc., you could say something like:

- Estando com febre, o Pedro faltou às aulasPedro missed school because he had a fever (Being with fever, Pedro missed classes)

- Consegui comprar uma televisão nova fazendo horas extraordináriasI was able to buy a new TV (by) doing extra hours

- In other words: Because I did extra hours at work, I was able to pay for a new TV.

Consequence

Similarly, the gerúndio can also appear in the clause which describes the consequence of the action described in the main clause, so naturally that is at end of the sentence. This use is somewhat rare, but you can replace conjunctions like pelo quetherefore , de modo queso that, in such a way that , etc., as in:

- Nós comemos demasiado, sendo impossível sair da mesaWe ate too much, so it was impossible to leave the table

Condition

Instead of using the conjunctions seif and casosupposing, in case to express a condition, we can go with the gerund. In most cases, it’s at the beginning of the sentence:

- Ficando sozinhos, os cães começam a ladrarIf left alone, the dogs begin to bark – “Staying alone…”

- Não tendo positiva no teste, tenho de repetir a cadeiraIf I do not pass the test, I have to repeat the course – “Not having positive on the test…”

Concession

The gerúndio can sometimes replace conjunctions like emboraalthough and apesar deeven though, despite . However, it should be used with the conjuction mesmoeven, indeed in order to make the meaning of concession clear.

- Mesmo estudando todos os dias, tirei má nota no testeDespite studying every day, I got a bad grade on the test

Replacing the Conjunction e (and)

Above, we’ve talked about gerund being used in dependent clauses but it can also be used to connect two coordinated clauses, in place of the conjunction e (and).

Above, we’ve talked about gerund being used in dependent clauses but it can also be used to connect two coordinated clauses, in place of the conjunction e (and).

For example:

- A Raquel vai jantar fora, ficando o Pedro em casaRaquel is going out for dinner, while Pedro stays home

- Os habitantes fugiram do fogo deixando tudo para trásThe inhabitants fled the fire, leaving everything behind

(It’s possible, in these cases, for the gerund to also have one of the values mentioned previously, particularly the time value. For example, in the first example shown above, Raquel is going out and Pedro is staying home at the same time.)

ir + gerúndio

Using the verb irto go with the gerúndio helps us express a sense of progress or gradualness. This is one of the most common ways of using the gerund in European Portuguese. Here are some examples:

Using the verb irto go with the gerúndio helps us express a sense of progress or gradualness. This is one of the most common ways of using the gerund in European Portuguese. Here are some examples:

- É uma questão de ir passando aqui na lojaIt's a matter of stopping by the store – This would imply that it’s a matter of stopping by the store probably more than once (a repeatable event).

- Fomos fazendo obras cá em casaWe kept doing (construction) work here at home

- Vai-se andandoIt's going – Common expression to say that life’s not good, not bad, just “going”.

Sometimes, the use of ir + gerúndio is basically the same as using a simple verb tense:

- Vou andando para casaI'm going home and Vou para casaI'm going home both mean the same thing. (Remember that andando doesn’t necessarily mean walking: How to Use the Verb Andar.) It’s just a common expression you can use just before saying goodbye to someone.

- Fui lendo o livro aos poucosI read the book little by little is practically the same as Li o livro aos poucosI read the book little by little , because of the adverbial phrase aos poucos, which already gives a sense of gradualness.

What is the difference between using the verb IR with the gerund, using IR in perfeito or imperfeito?

I’m not sure if this was your exact question, but as mentioned in the Learning Note, with the gerund, the verb IR is just there as an auxiliary verb to indicate gradualness and/or repetition. So the meaning of the sentence is defined mostly by the main verb:

– Eu vou estudando todos os dias até o exame (I’ll be studying every day until the exam)

– Vai vendo o estado do pedido, por favor (Keep checking the status of the order, please)

This is completely separate from using the verb IR alone in the pretérito perfeito (simple past) or imperfeito (imperfect past/past continuous), where it’s the meaning of IR that gives sense to the sentence:

– Eu fui à praia (I went to the beach – simple past)

– Eu ia à praia todos os dias quando era criança (I used to go to the beach everyday when I was a child)

If I misunderstood your question, please let me know here or via our support channel.

Hello Joseph. Thank you for for response. My original question was not expressed well. I am wondering about the difference between, for example, eu fui passando and eu ia passando Thank you for your thoughts on this.

Olá, Marge. It’s a subtle difference. The simple past is for when you want to express that the action has clearly ended in the past, and describe it with a distant outlook. For past actions that you want to describe with more proximity, as if going back in time to narrate it in almost “real time”, and without a clear sense of closure (i.e. the action might have lasted indefinitely, or it might have ended, but you’re not focused on that), you use the imperfect. That’s why the imperfect is a common tense in narrations/stories.

– Eu fui passando no hospital diariamente até ele receber alta (I passed by the hospital every day until he was discharged)

– Na altura, eu já ia passando por aquela rua com frequência (At the time, I was already passing through that street frequently)

Interesting. It seems like the use of gerundium in portuguese and german is nearly the same. Only the different use in the english laguage creates the problem😉

Hey Joseph!

I ‘ve seen sentences like the following:

“Vai chamando o táxi que eu já desço.” or

“Vão andando que nós estamos quase pronto.”

but still can’t translate the gerund and can’t get why we use “que”.

Thank you!

Olá! The gerund here is a call to start an action, so you can translate these examples as something like “Go ahead and call the taxi, as I’ll be right down” or “Go ahead and start walking, as we’re almost ready”. “Que” works as a conjunction here, connecting the two clauses of each of these sentences. However, the sentences are also understandable without it, so it’s not a critical element.

– Vai chamando o táxi; eu já desço

– Vão andando; nós estamos quase prontos

In the “Consequence”, you gave two ways to express:

1. Nós comemos demasiado, sendo impossível sair da mesa.

2. Comendo demasiado, foi-nos impossível sair da mesa.

Why is the verb “ser” reflexive in 2 (“foi-nos”) but not in 1 (“sendo’)?

Olá 🙂 In the first sentence, the object pronoun isn’t needed because the first clause already establishes who you’re talking about. In the second sentence, since the opening clause doesn’t give you any detail, it’s helpful to add the object pronoun in the second clause for clarification.

Can I rewrite the second sentence in personal infinitive instead? i.e.

“Comendo demasiado, foi impossível sairmos da mesa.”

Yes, you can! Either way, the examples under ‘Consequence’ sound rather academic. In casual conversation, we’re more likely to say something like “Comemos tanto que foi impossível saírmos da mesa”.